Plazas for the People

Can we build equitable smart cities?

Certainly there are instances in which specific interventions directly improve life for low-income communities (the Metrocable and escalators in Medellin come to mind), but too often, smart city policy skews towards idealism.

Mexico City, for example, is often named one of the top smart cities in Latin America. But some of its smart city initiatives — building technology meant to counteract smog, for example — are slow to reach the sprawling neighborhoods outside of the city center. These are disadvantaged communities in which small changes like clean water and better transit could mean big benefits.

The same problem exists in New York City, and the local government’s response has been mixed. On one hand, the Connected Communities program aims to increase internet access in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty. On the other hand, CitiBike has been widely criticized for its failure to achieve inclusive coverage.

The fair and equitable distribution of smart city policy worldwide is a gargantuan and multi-faceted problem, and it’s one that I alone cannot answer. But what I can do is analyze one teeny tiny part of the equation:

Is the New York City Plaza Program providing plazas to all communities, regardless of income?

The NYC Plaza Program

Transportation is a key component of smart city infrastructure. By using real-time traffic data to optimize traffic flows, intelligent transportation technology can improve safety and identify areas for redevelopment.

The NYC Plaza Program addresses these points. Under the program, the NYC DOT works with nonprofit organizations (often business improvement districts) to transform dangerous intersections or underused streets into vibrant public spaces. This type of placemaking is a growing trend right now, notably in Paris.

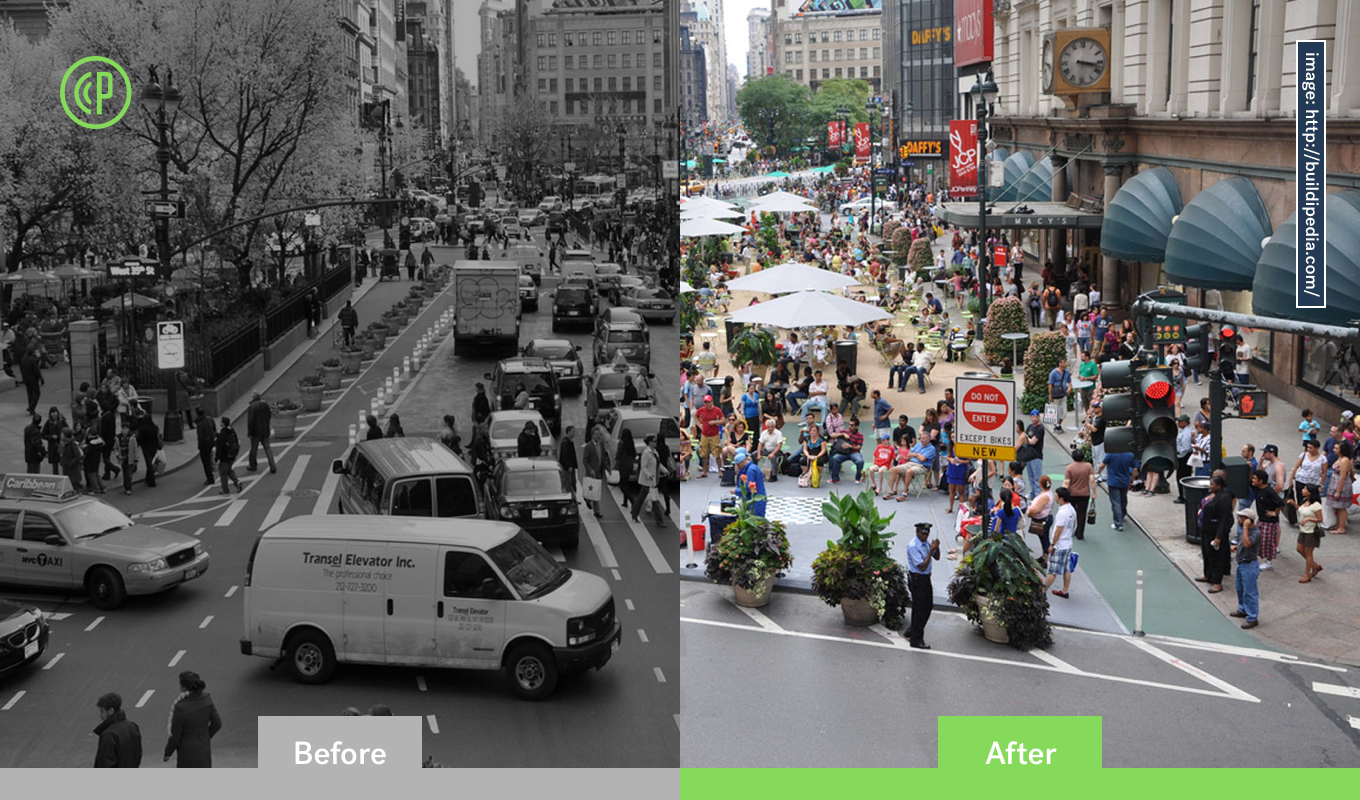

The typical NYC Plaza Program site reimagines a dangerous intersection. Credit: New York Times

One of these projects, the 34th Street pedestrian plaza, is shown in the header. During the predesign phase, Vornado used Placemeter to determine peak traffic volumes, times, and areas. The DOT and design team used the data to create a safe, social space.

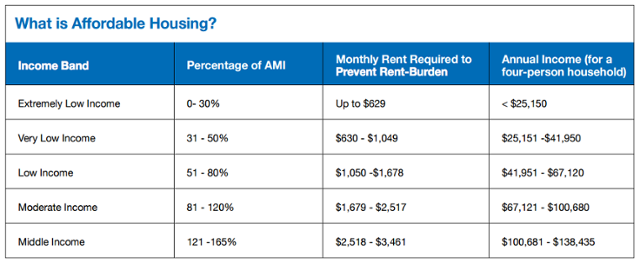

Under the program, nonprofit organizations propose plaza sites through a competitive application process. Applications are evaluated according to the City's strategic goals as presented in PlaNYC. One of the criteria is income eligibility: applicants received additional points for proposals located in neighborhoods where the Area Median Income (AMI) qualifies as low- or moderate-income.

"Housing New York: A Five-Borough, Ten-Year Plan" (PDF)

How evenly did this process distribute plazas throughout areas with low- and moderate-income households? To answer this question, I gathered census data and open data from the DOT to do geospatial analysis in CartoDB.

Open Data And Census Data

I used three datasets in my analysis:

- Shapefile of New York City’s 2010 Census Tracts, without water area, from New York’s punniest open data source: Bytes of the Big Apple

- Median Household Income, Census Tract Level, ACS 2014, from the American Fact Finder

- List of Plazas in the NYC Plaza Program, from the NYC DOT

Something to note: the list of plazas came in PDF format. Ben Wellington of I Quant NY has noted that agencies sometimes claim open data policies but inhibit access to the data by providing PDFs, which makes large datasets difficult to scrape. I can’t say whether or not this is the case with the DOT, but I didn’t have to worry too much at this point, because I found a free and easy online PDFscraper to convert my 73 records into csv format.

Geospatial Analysis

The first step was to join the census tract polygons with the income data. I cleaned the data and joined the datasets in CartoDB, and made a choropleth of the results.

Next, with some help from Avi and a Google API, I geocoded the plazas.

Remember how I couldn’t say whether the DOT had intentionally obscured their dataset? Well, when I came to this step, it started to feel like they did: 44 of the 73 records listed Bruckner Boulevard as a cross street, but only one of them is actually on Bruckner Boulevard, and nine of the plazas were listed in the incorrect borough. But hey, maybe they just had a tired intern doing manual data entry.

These errors confounded the geocoder, so I had to fix many of them by hand. But I did eventually find all the intersections, and I even added a bunch of them to Google Maps. (Search the map for New Lots Ave Plaza!)

The Plaza Program wants to ensure that all New Yorkers are within a 10-minute walk of green space, so I analyzed the area within a 10-minute walk of each of the project sites. A quick internet search told me that a standard conversion for this walk was 800 meters, so I created an 800-meter buffer around each plaza. I then did a spatial join between the new polygons and the census/income polygons to find the average of the median household income that fell within a 10-minute walk of each plaza.

I exported the results of this buffer and took them over to Plotly to make a histogram.

According to DeBlasio's Housing Plan, "Housing New York: A Five-Borough, Ten-Year Plan", a household of four making between $41,951 and $67,120 qualifies as "low-income". Under that definition:

54.79% of the current Plaza Program projects are located in low-income areas, suggesting that the DOT is serving all New Yorkers equally.

The multimodal distribution of the graph is interesting — it implies that the "moderate" income level ($67,121 – $100,680) receives a low proportion of plazas. However this may simply be due to the fact that the bracket is a small one in comparison to the low- and middle-income groups.

Areas For Further Analysis

This research could be supplemented by giving weight to each tract's median annual income based on population density.

Better yet, if I had that weighted data plus full Placemeter coverage of New York City's intersections, I would be able to determine the busiest intersections in the most populated areas, and the DOT could use that information to select sites for the next round of projects.

Placemeter is hard at work building partnerships with municipalities across the globe, so I look forward to analyzing more cities in the future!